We’re in search of detail and history here at Forgotten Fiberglass. Either directly from the folks and their families who were creating the history, or from first person accounts as narrated by authors in vintage automotive magazines. Today’s article is of an extremely high caliber and I started looking at the magazine it appeared in with a greater level of interest: Car Life.

I’m still learning about Car Life Magazine, but several things struck me as I reviewed those who created it. Let me share a list of names from the inside pages. Editorial Director: John Bond. Business Manager: Elaine Bond. Contributors: Bill Frick, and Strother MacMinn.

These were some of the most significant names of the times and helps explain the high level of work within the magazine. As many of you know, John Bond was owner and editor of Road & Track, but this was “Car Life Magazine.” What was the connection?

So as you might guess, I’m off on another project to learn more about this magazine and what it had to offer. No doubt you’ll be hearing more about this magazine as we continue our march of research into the depths of fiberglass specials and sports cars.

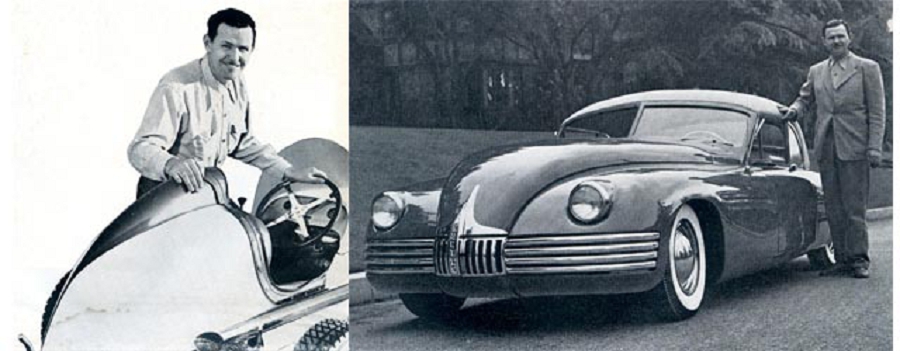

This particular article focuses on Frank Kurtis and his accomplishments with his company: Kurtis Kraft. It’s a great review that takes us back to 1920 when he first started fiddling with cars and their design.

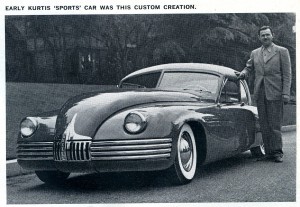

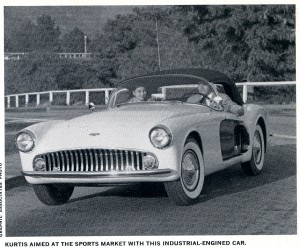

Frank designed and built a number of cars we’re interested in including the Kurtis Sports Car in ’49 and ’50 – the first production car to utilize fiberglass components for its body (front fenders, rear fenders, hood and trunk – all could be fiberglass if configured that way). He went on to build other significant race and sports cars and his last fiberglass sports car was the Kurtis 500M.

Let’s see what author W. Lee Tomerlin had to say about Kurtis and his success throughout the years in the sports car and race car arena.

Frank Kurtis: Kompetition Kars

By W. Lee Tomerlin

A man sits on the pit wall, looking out over 33 of the fastest racing cars in the world. He is an imposing figure, 6 ft. 4 in. tall, 200 lb.–and yet, by his very reserve he manages to remain inconspicuous. As his eyes pass over these cars–these brute monsters of speed–lingering on significant details, features of design, engineering and safety, he smiles with pleasure and satisfaction.

Why not? Of the 33 cars ready for the 41st Indianapolis Memorial 500, 24 have come from his brain, are the work of his hands. And before the afternoon is over, his cars will have taken the checkered flag first through 13th, in order. A parade. Though the thought would never cross his mind, he is the undisputed King of Indianapolis. He is Frank Kurtis.

That was 1953, the year that Billy Vukovich showed the way in his Kurtis-built Fuel Injection Special at an average speed of 128.74 miles per hour. But it was only one of the many years in which Frank Kurtis looked out over starting fields comprised mainly of cars he had built, cars that continued to bring home the bacon, race after race, cars that set and broke records in such rapid succession that it dulls the observer’s interest just to read down the list.

However, suddenly, inexplicably, in 1958 there were fewer Kurtis Kraft cars entering the 500 and even fewer winning it. By 1961–the running of the Golden Indy–there were only six cars left to carry the famous marque around the old brickyard.

The reason does not lie in the cars. It has to do, rather, with Frank Kurtis’ personality: his ideals and principles and, ironically, his love for Indianapolis. “I guess Indy was my first love affair,” Frank remembers, smiling in his self-conscious way. “I was 12 years old, and we’d just moved out to California, where racing was a way of life.”

The year was 1920, and the “Golden Age of Racing” was just under way. Men like Milton, DePalma and Murphy were burning up the Beverly Speedway in their Duesenbergs, Frontenacs and Durants. Foreign cars still dominated Indy and it was every big-name driver’s ambition to win there. “I guess it became my ambition too,” Kurtis says, “only I wanted to build the cars that won!”

The year was 1920, and the “Golden Age of Racing” was just under way. Men like Milton, DePalma and Murphy were burning up the Beverly Speedway in their Duesenbergs, Frontenacs and Durants. Foreign cars still dominated Indy and it was every big-name driver’s ambition to win there. “I guess it became my ambition too,” Kurtis says, “only I wanted to build the cars that won!”

His first car-building effort (at 14) as an old Model T Ford, assembled from junkyard parts. Frank’s natural flair for mechanics, plus training from his father, who was a Czech blacksmith, enabled him to reassemble the chassis, suspension, engine, brakes and steering gear from their ruined condition. Then came the question of a body.

Few of the available wrecks had whole body sections, but that didn’t daunt Frank Kurtis. With moral support from his younger brothers (Andy and Bill) and no other outside help, he had the whole job finished in less than three months. Today, Frank will admit that the result was a little crude: “But, at the same time, I don’t know when I’ve been more proud than I was then, sitting in that old Ford.”

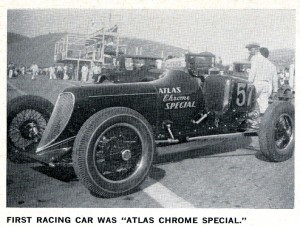

Frank had quit school the year before to go to work for Don Lee, race car owner, and to study mechanical drawing at night school for four more years. By that time he had hundreds of cars designs, most of them impractical, but all valuable in terms of experience. Five years later, he built his first racing car, a roadster.

“In 1930, roadsters held about the same position of eminence that sports cars now enjoy,” says Kurtis. “Outside of Indy cars and midgets, they were about the only machines raceable.” His proved even more “raceable” than most, and remained a top contender for years.

Prior to the beginning of World War II, Kurtis seems to have measured the span of his life not in years, but in relation to his cars and designs: “I opened my own shop, oh–a while after I built that roadster…” The year, for the more conventional timekeeper, was 1933. The shop was in Los Angeles, and it was here that Kurtis began to make a name in racing.

From the spotless floors and well-ordered workbenches poured more than 800 midget racers destined for fame and success on almost every American track. The name Kurtis Kraft became synonymous with victory; but to Frank all this was mere preparation. His dream remained intact: to build “500” racers. His first chance to build a full-size racing machine came in 1939.

“It was the break I’d been waiting for” he says. “Even though I had made it with midgets, at Indianapolis nobody had ever heard of me. I’d gotten enough money to build one car, and I figured ‘This is it. If I flunk out, I’ve had it’.” And one week before post time, it appeared that was exactly what he was going to do.

Ronnie Householder, a driver who has since made his name in other phases of motor racing, was scheduled to pilot the car. “He was getting along fine in trial runs. building up speed and settling into a groove,” Frank relates. “Then, on this one lap, as he was coming out onto the back straight–Wham! He hit the wall and flipped over three times.”

The car seemed far too badly damaged to make the grid in time, and to make matters worse, Householder had decided he’d had enough, though he had escaped, miraculously, unhurt. “When I got to him,” Frank recalls, “he was standing there, looking back at the wreck of the car. Then he saw me. ‘That’s it, Frank,’ he said, ‘I’m through with Indy’.”

Without a driver, and without much of a car left, Frank appeared to be out of the running for 1939–and because of the war, until 1946. But Kurtis was not through; he went to work on the twisted wreckage of his car, and began looking for another driver. By the deadline for qualifying, the Kurtis special was running, and Billy Devore had agreed to run it. With Billy at the wheel, the car ran the full 200 laps without a fault, and crossed the finish line in 10th place–a standout performance for a builder in his freshman year. “It wasn’t bad for a start,” he can still say, 123 Indy cars later.

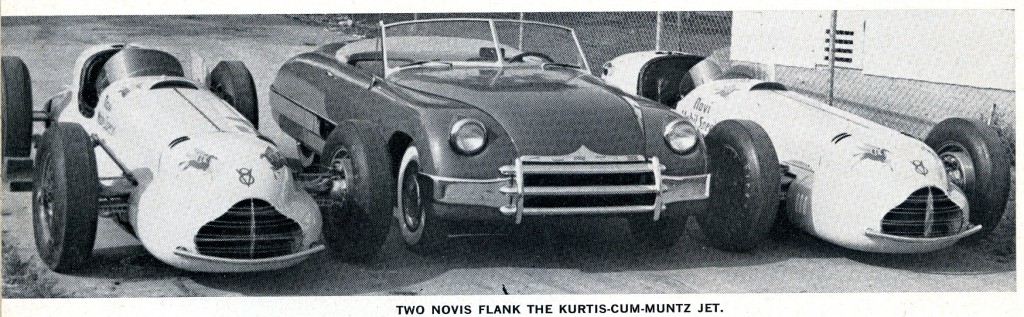

The war years were idle ones for most car builders, but not for Kurtis. He used them at his Los Angeles plant to formulate new techniques and to perfect his design principles. By the time racing resumed he was ready, with three cars in the pits–one of them the first of the brilliantly-conceived but ill-fated Novis.

Kurtis was to build four of the Novi-powered front-wheel-drive cars and later to transplant two of the engines into his conventional chassis. Although tremendously high in potential, these cars seemed doomed to pre- or in-race mechanical failures and accidents, and have never run in the top money.

“I’ve always believed that luck plays a more important part in racing than most people realize, or will admit,” Kurtis says. “The Novis are one example: they were consistently the fastest cars in the race; and we had good drivers, too. Nothing! Or take Billy Vukovich. Put him in the Fuel Injection Special–one of the finest cars I ever made–and then watch luck take the situation right out of your hands.

“As it did in 1955,” Frank says, soberly. “For two years (1953-54) Vuky guided the Special to victory, and in 1955 he was leading the field, well ahead of his competition. Then suddenly, for no explained reason, he spun out of control and crashed. Just plain, impossibly bad luck!” Frank insists. “Why, Vuky was the best driver who ever sat in one of my cars–but he didn’t have the luck.”

How does a car-builder feel when a man is hurt or killed in one of his cars? Kurtis answers this question with grim sincerity. “It’s always the same: terrible. The first thing that comes to my mind when I see an accident happen is ‘What a hell of a business to be in!’ And if a driver is killed, I’ve almost always lost a close personal friend.”

Doubtless, this attitude has been the source of Frank Kurtis’ almost fanatical effort to build safety into his machines. And it has led to some of his most bitter disappointments.

Doubtless, this attitude has been the source of Frank Kurtis’ almost fanatical effort to build safety into his machines. And it has led to some of his most bitter disappointments.

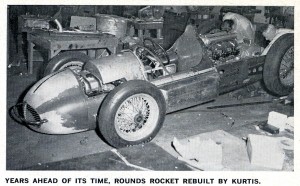

“For instance, in 1950 I rebuilt a rear-engine car (owned by Nat Rounds) and introduced on it a new soft-suspension system–much like Rodger Ward’s car this year. It was a good system, designed to keep driver fatigue down and safety up. A top-name driver tried it out–just one lap–came in and said he couldn’t get the feel of it.

He wouldn’t give the car a chance, you see–and after he’d said that, neither would anyone else.” “This was one instance of what Frank calls “resistance to any change, by the Indianapolis camaraderie,” which he says he encountered almost every time he tried to introduce something new.

“Only during my biggest years was I able to include some of my ideas–the least radical ones–in my cars,” says Kurtis. Among the Kurtis “firsts” still in use on almost all Indy cars are: transverse torsion bars, the offset engine, fiberglass sheathing for fuel tanks, fiberglass body panels, and the now-popular “roadster” design (as it was dubbed by Vukovich in 1953).

Kurtis also built two diesel-powered cars which ran in 1951 and ’53. Both placed well in qualifying, but because of mechanical difficulties neither finished well; and they were not raced again. “Eventually,” says Kurtis, “most of my ideas were accepted, but the thing that discouraged me was that it never got any easier. I would have just as much trouble trying to introduce something new today as I had in 1939.”

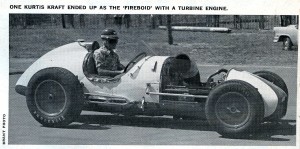

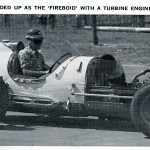

Two years ago, a buyer showed interest in one of Frank’s most ambitious designs: a rear-engine turbine-powered car, the final plans for which were completed in 1954. “My buyer was hot, but Indy was cool,” he relates gloomily. “We sent in specs for approval, and when the response came–a sort of ‘Dear John’ letter out of context–the buyer took one look at it and said, ‘Sorry, Frank; I’d like to take a chance, but…’

And I couldn’t blame him; not many people can afford to pay out between $25,000 and $50,000 on a car if there is the possibility of an official snag later on.” He shakes his head, remembering. “It was faster and safer than anything else I’ve ever designed. If it had run at Indy in 1959, I’d be turning out 10 or more turbine racers every year, right now. I’ll bet there wouldn’t have been a single reciprocating piston engine left at Indy by ’62!”

According to Kurtis, it has been just such experiences as these that have caused him to cut down on production so much in recent years. His Indy car output is now only about 3-4 annually.

Does this mean that in another few years he will have retired from Indy altogether? “No,” he says positively. “I still love Indy and I guess I’ll keep building cars for it until the day I die; but I’m not going to keep on building the same car, year after year. I’ll go into full production when they begin allowing me room to progress technically.”

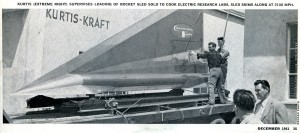

If any man is qualified to make such technical progress, it is Frank Kurtis. His genius is wide-ranging; since opening his first shop, he has turned out streamlined housetrailers, Jeeps for World War II, jet aircraft servicing vehicles and a land-rocket sled that has traveled in excess of 2100 miles per hour.

He designed, tooled for and built prototypes of two sports cars, one of which clocked 142 miles per hour at Bonneville in 1949 and continues to run in–and win–sports car races today. What does the future hold for 53 year old Frank Kurtis? According to all the evidence, a very great deal.

He designed, tooled for and built prototypes of two sports cars, one of which clocked 142 miles per hour at Bonneville in 1949 and continues to run in–and win–sports car races today. What does the future hold for 53 year old Frank Kurtis? According to all the evidence, a very great deal.

When not at his Glendale home with Arlene (to whom he has been married for 33 years) and his children (Arlen and Eilona), he is as busy as ever at the drawing board. In production are quarter-, half- and full-midget racers, karts, Indy-car parts and a wide range of multi-purpose machines. Also in the works–and soon to be seen on Southern California sports car tracks–a small, jewel-like Class H car, the first of several Frank plans to produce. And on the horizon: Formula I.

“These cars really excite me,” Frank confesses. “The Europeans have made tremendous strides technically and in terms of safety in the past few years. I think the reasons for this are clear: by allowing the factories a free hand in design and by reducing the displacement limit from 2500 cc to 1500 cc, the manufacturers were forced to look for new ways to get more speed from less horsepower. And they did it! Just look at Jack Brabham’s show this year at Indianapolis…” (See Car Life, June ’61.)

Both Brabham and the Cooper were new to the brickyard, and it was generally felt that they were wasting their time: They were giving away an average of 130 bhp; they didn’t have any high-pressure refueling equipment, and Brabham is the type of driver who never pushes his car to the limit. Yet he finished in ninth place at a speed which exceeded that of the 1958 winner! And 21 of the front-engine cars failed to finish at all, making his showing even more impressive.

Kurtis feels that we are seeing the end of an era at Indianapolis, and the beginning of a new one that will be brighter, faster and safer. He is already contracting to build an Indy car with a brand-new Novi engine–in the rear.

If Kurtis is right; if the previously impenetrable wall of inflexibility at Indianapolis is finally starting to crack and crumble, there might well be a new generation of Kurtis Kraft cars burning the bricks at the Memorial Day 500-miler, heralding the triumphal return of Frank Kurtis, the King of Indianapolis.

Summary:

This is the best review in a magazine that I’ve seen so far of Frank Kurtis and Kurtis Kraft – and it was done back in 1961 when Frank was 53 years old. That age is looking younger and younger to me. Getting information from the primary source as close to the period in time that we are interested in provides the best insight possible into the man and his cars.

I have the greatest respect for Frank Kurtis and Kurtis Kraft and look forward to sharing long-lost articles about him, his company, and his cars here on Forgotten Fiberglass.

Hope you enjoyed the story, and until next time…

Glass on gang…

Geoff

——————————————————————-

Click on the Images Below to View Larger Pictures

——————————————————————-

This is a really great story with excellent quotes from Frank on what he really experienced in all his time racing. It goes to show just how hard headed the Indy regime is and how in hind sight it is such a shame to see that an American had plans to race a car their with a mid engine layout a full decade prior to the English coming to Indy. Oh, what might have been…..

Thanks for posting this for me unknown story about Frank Kurtis! I have been focusing on the early days of customizing lately, and Franks Kurtis is an important player in this field! This story gave me some new details on Frank.

Sondre Kvipt

Kustomrama

What a terrific article about Frank! It is interesting that it mentions Nat Rounds “rear-engined rocket”. My partner Doc took me to meet Nat and see his car in early ’54. He had failed to qualify at Indy for a couple of years, but was still trying. Victress did the first fiberglass sheathing for Frank’s gas tanks, using a clever method of Doc’s invention in the pre-epoxy era. We also fabricated quarter and half-midget bodies, and I think a few midget tails, as well as parts for his Buick-powered jet-engine start-carts,and golf cart bodies. This article must have appeared about the time that Kurtis cars were going out of fashiion at Indy. One Memorial Day, about ’62 or ’63, Doc and I went to the Burbank Theatre to watch the Indy race on the big screen, and there was Frank Kurtis standing in the ticket line. None of his cars had qualified, and he saw no point in going to Indianapolis to see the race. It was rather sad, but it was an honor to sit with him and hear his comments as the race unfolded.

Merrill Powell

VP Victress Mfg. Co. Inc.